Do you have a habit of pain?

Photo by Hailey Kean on Unsplash

Pain is an essential part of life. It protects us by alerting us to injury or danger, such as touching a hot stove or pulling a muscle. However, pain doesn't always serve this protective function. For some individuals, pain can persist long after the physical injury has healed, creating what can be described as a "habit of pain." This concept, while not new, sheds light on how our nervous system can become "addicted" to the sensation of pain, even when no injury is present.

Many people have come to me in my practice over the years and in courses that I teach that have said, “I find it really strange. I injured my knee 20 years ago. And then I got over it. I'm fine. And now lately I'm getting exactly the same knee pain, but I haven't done any particular exercise that would create that. I don't have trouble walking up the stairs. It just hurts.”

Now, is it because there's a newly formed pain?

No, none of this is from an injury.

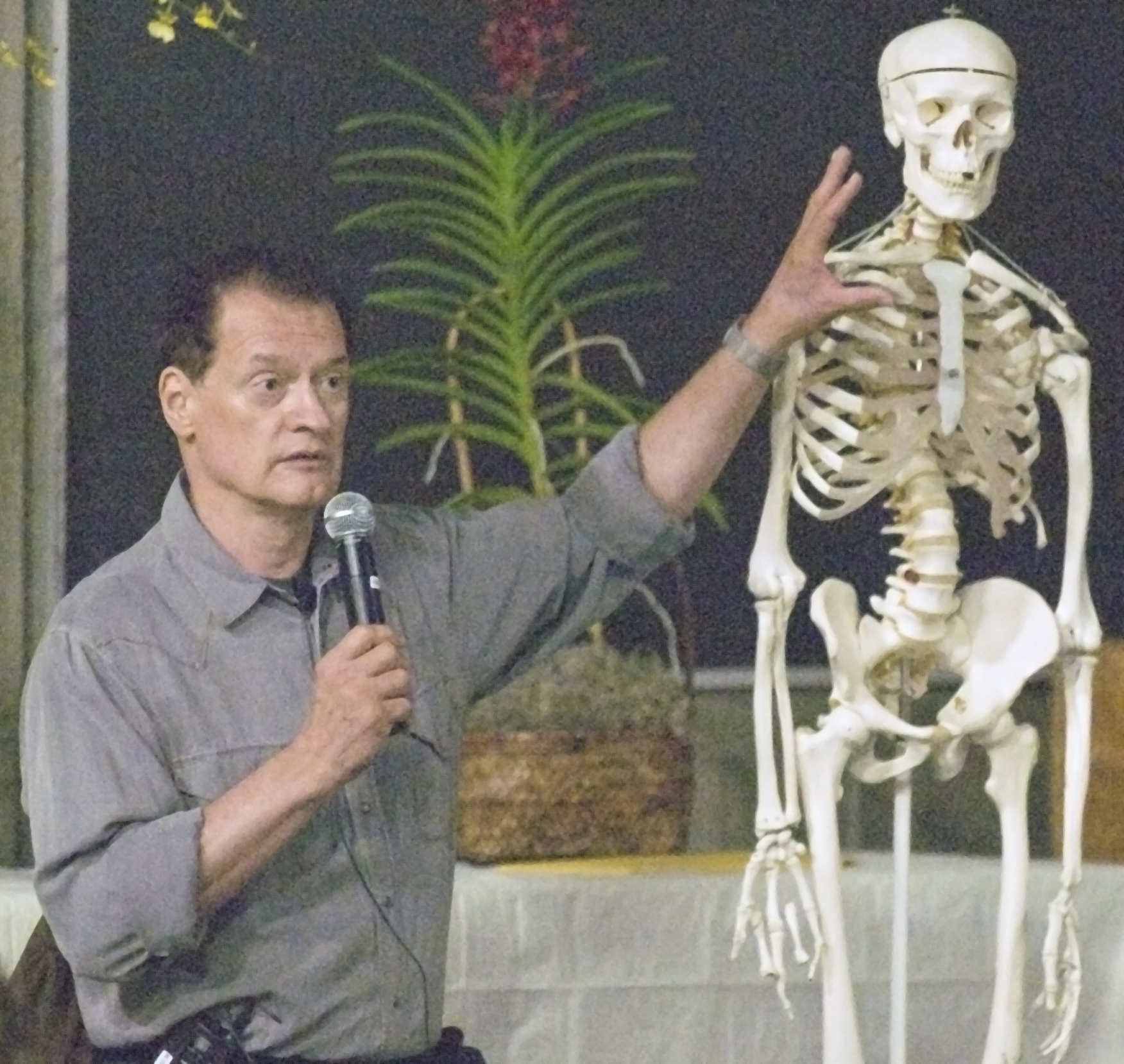

Your body is filled with nerve receptors—sensory receptors, called proprioceptors. Proprioception tells you, where are you in space? Where are your hands in relation to your mouth so that you don't stab your face with a fork, but get it in the mouth? When you take a step, what muscles do you need to use spontaneously to balance so you can take the next step? Your body's full of receptors for that kind of spatial awareness and body awareness of yourself in space.

Then, of course, you have pleasure receptors. We eat foods that are good and not necessarily good for our health, but hey, they're addictive, right? Oh, crunchy salt and pepper chips. How about things with loads of ice cream with saturated fats? There are a lot of things like this and people can become addicted to food altogether. Some people overeat and overindulge because that's satisfying. They get sensations that are pleasurable. Same thing with sex. Some people kind of overdo it, and they don't even realize they're overdoing it. They're just seeking to get a certain sensory satisfaction.

However, throughout your body, along with all the proprioceptors and other sensory receptors, there are also nociceptors.

Just as the brain can develop patterns around pleasurable experiences—like craving sugary foods—it can also form patterns around painful experiences, causing the sensation of pain to persist long after the injury has healed.

Nociceptors are specialized nerve fibers responsible for transmitting pain signals to the brain. These receptors are distributed throughout the body, and their function is to alert us when something is wrong, such as physical damage or inflammation.

Now, you have to understand that pain is a good thing. That sounds funny, doesn't it? I mean, pain is a good thing? Well, yes, it protects you.

The worst thing that could happen to somebody is to be born without adequate nociceptors. And what we know is, when that happens, they're in great danger. They could put their hand on a hot stove and not even realize it until they just singed themselves badly. People can also break a bone and keep on running not because they have will power. Rather, their nociceptors didn't respond. Later on, however, they might just be sitting around and they’ll get up out of their sofa or chair at night and move themselves in a certain way where the bone moves a little bit where it was broken, and suddenly there's a shooting pain, and they have no explanation for it because when they ran, it didn't hurt them. There have been marathon runners who ran on broken legs. They just never realized it until after the race.

This network of nociceptors is essential for understanding how our experiences of pain can become habitual. Just as the brain can develop patterns around pleasurable experiences—like craving sugary foods—it can also form patterns around painful experiences, causing the sensation of pain to persist long after the injury has healed.

We can have an addiction to the feeling that we get from pain.

Photo by Mitchell Hollander on Unsplash

The concept of being addicted to pain might sound strange, but it’s grounded in how the nervous system works. When pain becomes a habitual experience, the neural pathways that carry pain signals are reinforced, much like how habits are formed through repetition. Over time, this can lead to a situation where, even after healing from an injury, individuals continue to experience pain because their brains are so accustomed to the sensation.

Some people can go for a walk and feel, “Oh, man, my ankle hurts, my balance I was struggling with, my hip hurts. Ah, maybe I should go to a surgeon and have them take a look at my knees and my hips.”

Well, fine. And, you know, a doctor might find something wrong with your hips and knees.

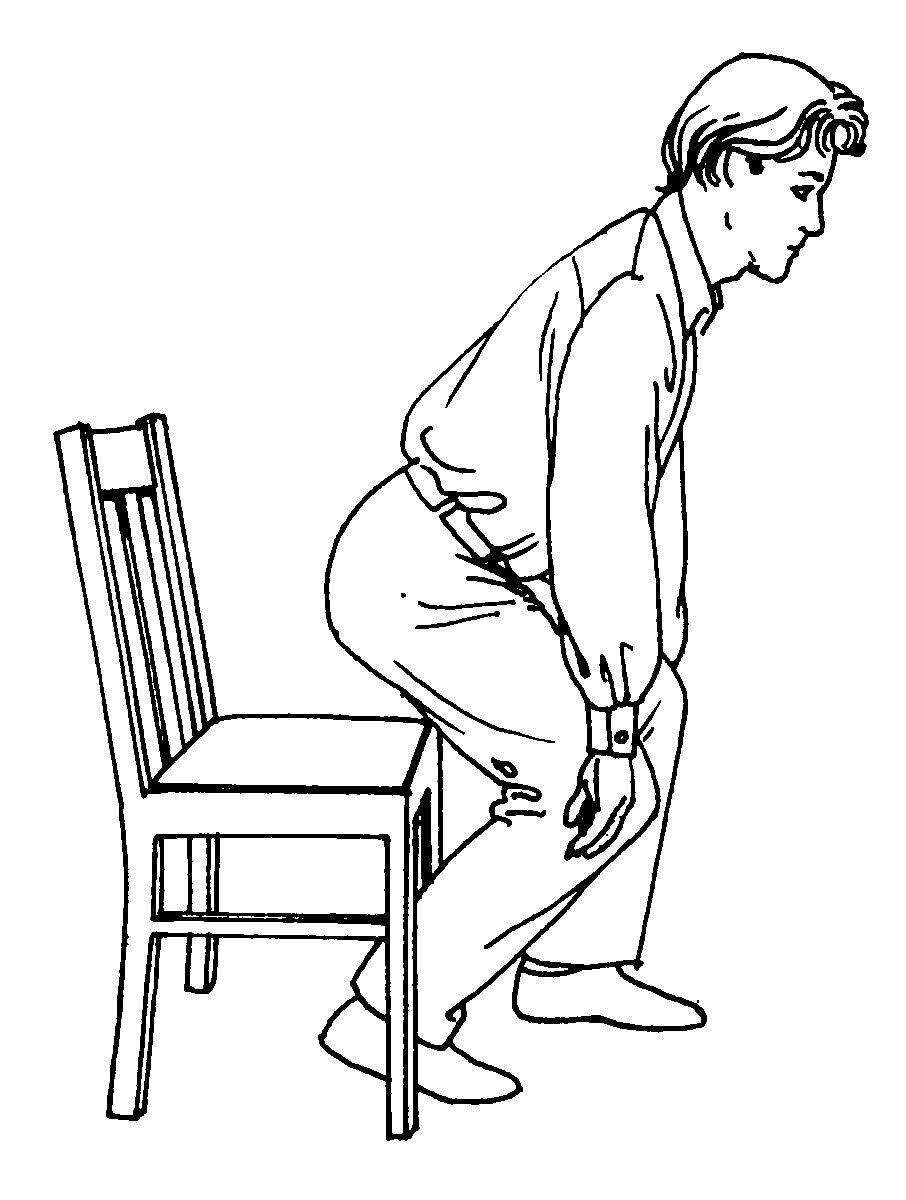

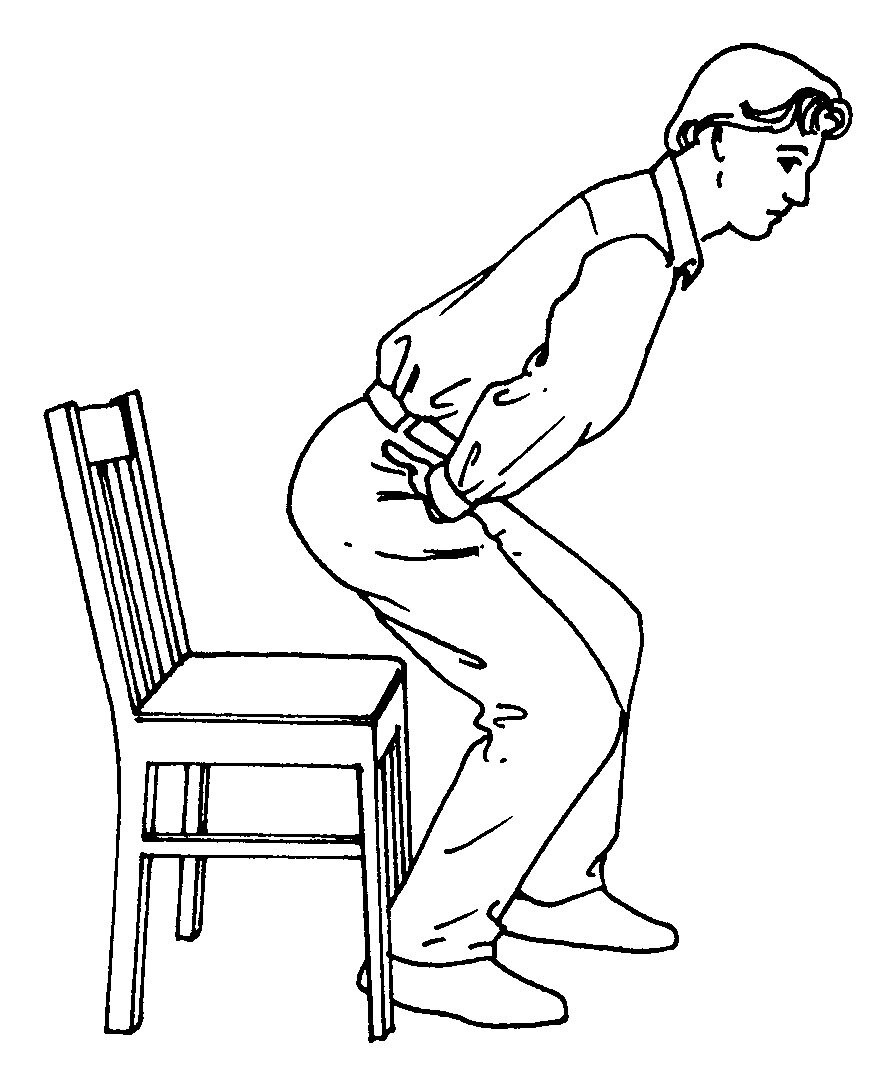

Years ago, when people had pain from their backs, right, they had a back problem. And the back problem means it hurt. And it hurt in a variety of ways. You know, bending down, picking something up, getting up out of a chair, a lot of things.

So with this problem, they began to go, “Well, what can I do about this except go to the doctor?”

And the doctor takes, let's say, an MRI and an x-ray. They look at the spine, and they go, “Well, you're fine. There's nothing wrong with your spine. We can't find anything. It looks perfect. You're lucky. The cartilage is intact. Nothing's slipped too much in your vertebra. Sorry, sir, but let's send you to physical therapy to do some exercises.”

Okay. But here's an interesting thing about nociceptors.

Now, that person, however, might have had a severe pain when they went to the doctor and got this information.

However, somebody else might get in a car accident, and it is terrible. And they got serious damage to their spine. Their back is hurting for a very good reason. Muscles are pulling hard to hold the bones together. And they get out of their car. The police have to help them out, get them into an ambulance, go off to the hospital.

And you'd wonder what the doctors would find.

Well, sometimes nothing.

They go to the hospital and they're in the same condition as the other person. This time, doctors can see damage of all kinds that's revealed in the x-rays and the MRIs and tests that might be run for them.

But actually, they're the kind of person to whom they become inured to their pain. They just don't pay attention to it much. And in fact, they heal very quickly and the pain goes away even sooner.

Discrepencies between these two examples led researchers to start thinking of pain in a different way.

The different experiences of pain can occur because the brain has formed what is often called an attractor well—a concept used to describe how certain patterns, including pain, can become deeply ingrained habits and difficult to break free from.

I get a lot of clients complaining that they just get out of bed in the morning and felt, “Oh, man, I must have been sleeping funny. My neck is killing me or my back is hurting me.” But maybe, their nociceptors are firing as they habitually do.

In an interview you find this out, that these kinds of things happen to this person throughout their life, and quite often. And you have to look at it as the nociceptors falling into what's called an attractor well.

An attractor well is a term, if you could think of a rock rolling along the ground, or a ball rolling around the ground. And somewhere in the ground, there's a well, a hole in the ground. And that ball heads for that well. And what's it going to do? It's going to roll into the well. It's not going to keep going over it. So it falls into the well. Now, how do you get the ball out of the well, you see?

That would be a question like, well, how do you have a solution for your pain? What do you need to learn? What do you need to feel or change so your nociceptors aren't screaming at you?

So, okay, you might find you've done something or other and you feel better. That means the ball would be out of the attractor well.

But whenever you roll that ball, it's going to probably go to the lowest point, and it's going to roll by itself easiest downhill a little bit. It doesn't have to be much, and it'll roll faster and faster and fall back into the well.

All of us have attractor wells.

Some of us have a shallow attractor well, and in fact, things don't stick, meaning, “Wow, that hurt. I remember when that really hurt. But actually, it's not bothering me anymore.”

Somebody else may have had a very mild strain, but it keeps hurting as a mild strain for 20 years, and some people even longer.

So that somebody whose attractor well is creating the habit of pulling the person's self, if you will, into pain.

All of this is part of what's called the neural matrix, meaning the matrix of varied possible ways that your brain organizes basic information about our body to us, like, “Ouch, that hurt. I shouldn't be touching a flame.” Or, “Ow, my knee hit something hard. Damn it.”

Or, “Oh, if I just avoid stepping a certain way, I stop hurting. Ah, I can walk now without a back pain. Great. What am I doing differently so I can learn from that and so I don't have to go to the doctor and I don't need any specialized treatment? Instead, I need to change the way in which I organize the pleasure and pain wells that are all part of what's called the attractor wells.”

In other words, some people, unconsciously, are attracted to pain. And it's a wicked problem.

Pain habits are devious. They're difficult.

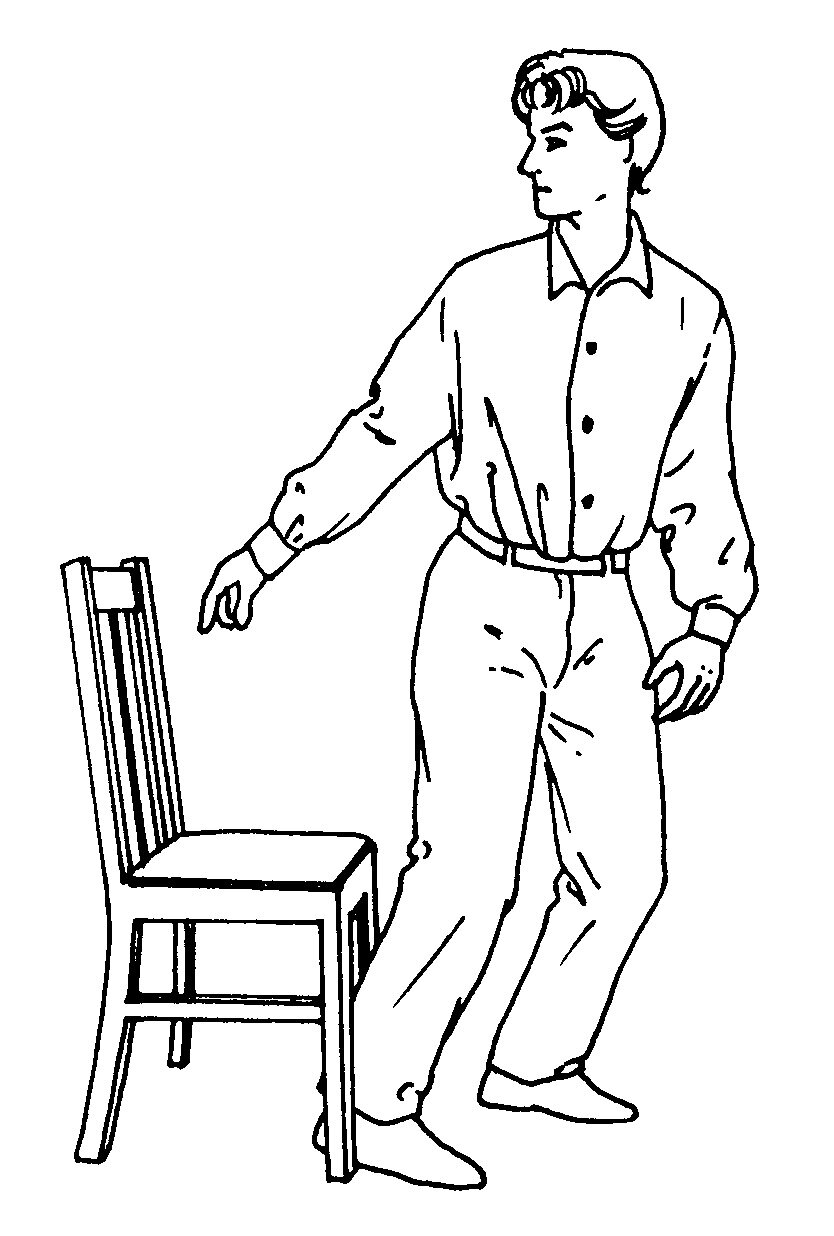

To reorganize your painful sensory habits, it’s helpful to work with a professional one-on-one, but one approach to get started is to return to the exploratory movement of your youth.

Check out Dr. Wildman’s video programs— Change Your Age, Embodied Balance, and Active Sitting— and books Change Your Age and The Busy Person’s Guide to Easier Movement.

The Power of Moving like a Child

For example, to move at all as a child, as an infant and a young child, you had to perform repeated movements again and again and again until you felt what you needed to do to, let's say, get your legs working and your trunk working so you could stand up, that kind of thing.

Now, you may think, what's the attractor well there? There are people who at the age of even 40, 45, look at the floor and go, “Oh, man, once I get on that floor, I don't know how I'm going to get up again without strain. It hurts so much. My back hurts. My knees hurt.” My whatever. Anything can hurt.

And that's a person for whom the floor becomes something like an attractor well. It pulls them in, and they go back to childhood. And it's like, “Uh-oh, I don't know what to do. I can't get up.”

Children cry over a lot of things. They fall down. They hurt themselves. They cry. However, I've never seen a kid, I've never heard of a child who cried because they learned to stand up.

Photo by Juan Encalada on Unsplash

That's a happy moment. That feels good, apparently.

So that's a great attractor well, therefore, for the child to have and carry throughout their life, including when they might want to lie on the floor at the age of 60 or 70 and get back up again.

So think about it. Do you feel that pain for you might be a habit?

Pain is a complex and necessary part of human experience, but it can also become a habit, ingrained in our neural pathways. Understanding how the brain processes pain and how we can retrain these pathways is essential for overcoming chronic pain so individuals can break free from any attractor wells of pain and live healthier, more comfortable lives.

The goal is not to eliminate pain entirely but to differentiate between protective pain and habitual pain that no longer serves a purpose.

I’d like to describe a case study of one of my patients and their encounters with the habit of pain.

I worked with a 60-year-old woman who had pains everywhere in their body. They had experiences of waking in the morning with extremely tight hands and itchy pains that they felt often in their skin. And stepping on the floor out of the bed for the first time in the morning was an unpleasant experience, meaning their feet didn't feel good and the beginnings of just bearing weight and having to walk those first steps were uncomfortable. She had pains everywhere. It was really not a matter of finding out which pains finally; there were just many of them.

Now of course, what I had to do was avoid having her hurt in relationship to my touching her and moving her.

I didn't trust her moving her own body at all because, in fact, every time she did, it hurt her in some way.

Lying on her back, I said, “Could you bend your knee on your right leg and could you stand your right foot on the table?”

And she could do it, but it was a great effort. Incredible stiffness in the breathing and in her face and chest. But she did it.

I thought, “No, no more.” So I moved her into that position. But I had to do it in a way that was felt by her nervous system as easy and hopefully, pleasurable.

I did this with many movements that you might call ordinary and fundamental movements of the human body that hurt her.

Finally, after only a couple of sessions, when she got done, she felt like weeping.

Now, at first, when I saw that in her face, I felt, “Uh-oh, did something go wrong here?”

But in fact, she was weeping from the relief that she felt and a sense that she could sense her body. She could just simply sense her body. Where she was in space, the pressure of sitting and her feet on the floor, the whole thing, she could sense herself without pain.

And that meant, for the first time, she could sense herself without having a sensation of herself related to pain.

Breaking that habit is really important. Now, she's an extreme case.

However, everyone might feel this way a little bit at times.

The secret ingredient to improving Body Intelligence and acquiring new skills

Something hurts. Let's just say it's a leg. A knee hurts. That's a common one, right? A knee hurts. And so the person can't do certain things well, right? It hurts to walk. It hurts to climb stairs, especially with the knees hurt. Downstairs, even worse.

And then we tend to go, “Well, it's a knee pain, maybe meaning there could be orthopedic damage at the knee.” That could be, but that's not true for a lot of people because I see clients whose doctor said, “No, their knees look fine on the x-rays and they're structurally okay.”

But they come to me with pain. They have to learn—and my job is to help them to learn—how they can move their pelvis differently, how they could stabilize on the other leg not stepping down to a stair. What are they doing in their back?

Let's say the left foot's going down. Well, then that means the right leg has to be exceptionally stable to allow them to land on the left leg without it hurting the knee. They have to control that with many muscles that they may not be aware of at first.

So it takes time. However, once they develop that greater awareness, they get the idea that they have control over their pain and they can develop their own pleasurable attractor wells. And so can you!

If you are looking for help relieving your pain symptoms, book a free 15 minute consultation with me, here.

Check out Dr. Wildman’s video programs— Change Your Age, Embodied Balance, and Active Sitting— and books Change Your Age and The Busy Person’s Guide to Easier Movement.