Why do some people get great benefit from resistance machines or weights, yoga, and rehabilitation and others derive little to no benefit or find exercise of any kind difficult and often painful? The answer lies in how we sense ourselves.

Exercise—whether for rehab, getting stronger, or having fun—should first require being able to sense your whole body when you work out or move at all.

As a movement scientist and therapist, I saw Sandra who had been hit on the passenger side of her car. The accident created an injury to her right leg and right hip. She presented to me with a limp and a barely mentioned irritation-into-pain in her right hand.

Sandra was aware of her limp and was afraid of it getting worse. The issues with her right hand, which she attributed to too many hours working on the computer, made it difficult for her to write or even type. She had been sent to physical therapy rehabilitation, but the exercises she received did little to benefit her and created more pain, so she stopped.

That she had a limp was obvious so I began to look for the invisible, a strategy I frequently employ.

I was interested in why she didn’t better use her other hip to balance the pelvis so the limp could diminish. Instead of giving her exercises for her injured right leg, I helped her to sense how she was using her left leg, her back, and her upper body (her arm swings, etc.). I helped her through a touch that would direct her to feel what she was actually doing with the rest of her body instead of being preoccupied with her right leg.

She was curious if I could help with her right hand and arm. Though her hand and arm were not injured in the crash, I began to understand the connection between the right leg and hip and the right hand and arm. In response to her accident, she reduced the motion of her head and neck, which in turn led to the stiffness and pain in her hand.

Sandra needed to feel the connections and integration of her body parts until she could sense the relationships as much as I could see and feel them. More than any exercise, she needed some Sensercise.

What happens after injury?

After any insult to the body, your brain will tend to withdraw sensation from the area that’s been damaged, in pain, rigidified, or collapsed. This is called sensory motor amnesia.

An insult to the body can be caused by anything from a car accident to an athletic injury. We also feel insults to the body when someone successfully insults us. A punch in the gut or a public humiliation tends to have virtually the same somatic effects: a sucked in diaphragm and a collapsed chest—a protection while waiting for the next insult.

In response to injury, our brain will try to protect us from pain—by developing a limp to allow a wounded hip to heal, for example. Right after an injury, this is helpful, but as time goes on, it can cement clumsy and stiff movement habits with wide ranging consequences.

All insults diminish our sensory acuity, which then leads to less coordinated movement, decreased spatial awareness, insecure balance, and can lead directly to further insults like accidents and re-injuries. Diminished sensory acuity helps explain why some people benefit from rehabilitation, yoga, or strength training while others do not.

To regain our sensory motor memory, we need to improve our body awareness through Sensercise.

As Sandra began to sense how she was using her entire body, including her breathing and the use of her head and neck to orient herself in the environment, her limp began to improve. Only after several sessions of altering her movement habits did I begin to work directly with the right leg or hip. After about a month, Sandra began to walk normally. She was startled to find that her right hand and arm pain disappeared. How could this be?

I gave her some Sensercise movement strategies. I asked her to intentionally reproduce the limp that she previously had and also to tighten her neck and reduce head motion as she had the habit of doing after her car accident. Her intentional limp created pains in her back and hip and her reduced head and neck motion ended up creating the stiffness and pain that she felt in her hand and arm. By exploring how she could create the pain, she discovered how she could not only diminish pain but also improve her movements because she sensed the integration of her body.

Rebuilding our sensory maps

To improve body awareness and help our brain to protect ourselves, we have to rebuild a sensory map of our body in the same way we originally built a sensory map of our body from the day we were born until somewhere in the beginning of adolescence.

How do we build and rebuild our sensory maps as needed? First of all, though something we call exploratory movement. A baby learns to explore all the time. Children explore not only with themselves and their own movements but also how their movements relate to playmates as well as adults. This involves continuously attending to kinesthetic information in order to know what movements to perform and how to relate to other people.

Here’s an example of how you can examine, sense, explore, and change your sensory map. Suppose you wanted to go from sitting to standing more easily. How would you learn to do it?

A typical exercise approach might say build stronger, larger thigh muscles. And then perform a regimented manner of moving up and down from a chair to standing then sitting. This would be called performatory movements. In other words, take the internal understanding of yourself for granted and exercise your habits accordingly.

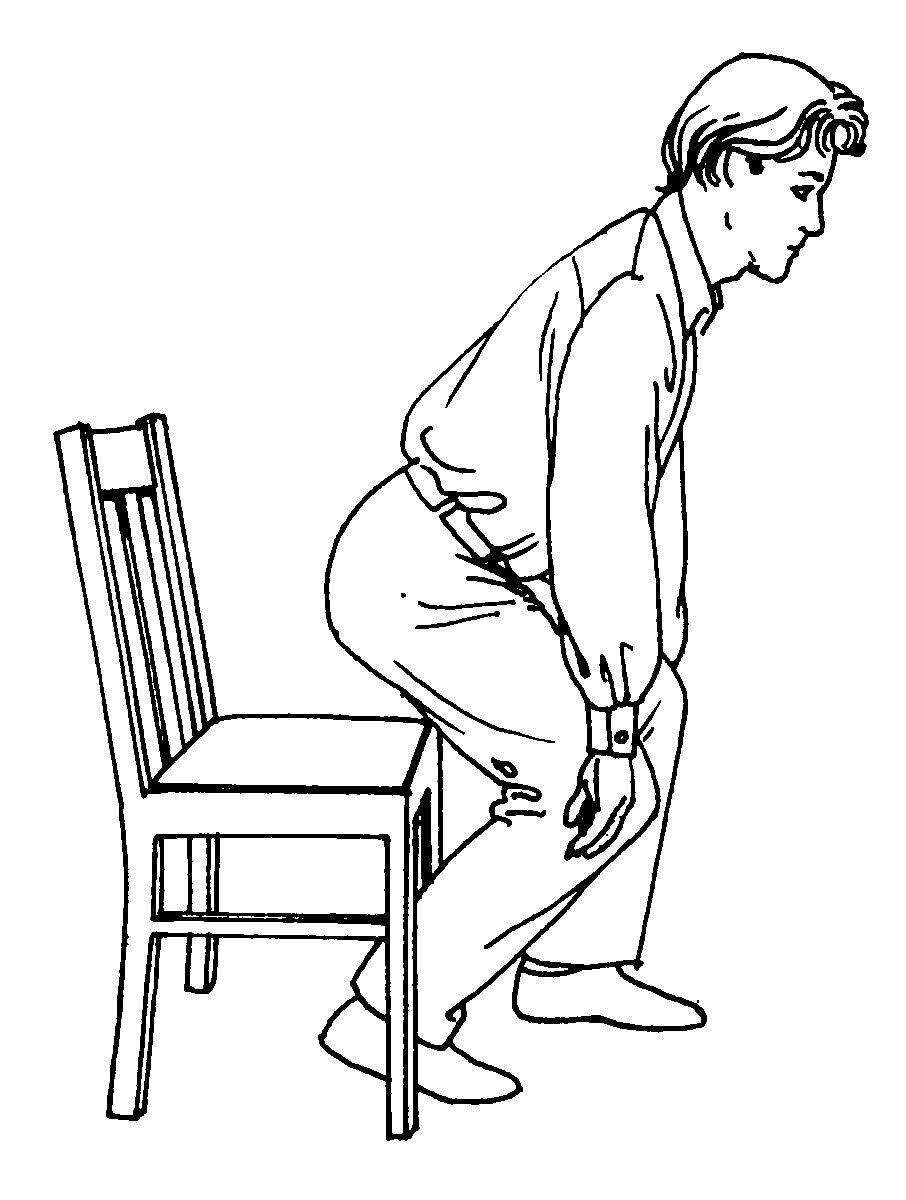

A more exploratory approach would be to first sense in a sitting position, without back support, if you are sitting with equal weight on each buttock and sitting bone? Try standing with your feet well in front of your knees. See if you can do it. This involves a lot of momentum as well as strength as you throw yourself forward. How about exploring the same movement with your feet closer to yourself than your knees. As you rock forwards on your sitting bones, do you find it easier to stand? What about if you explored the best position for your feet? Maybe one foot could be a little closer than the other. Can you discover in this way the best place for your feet?

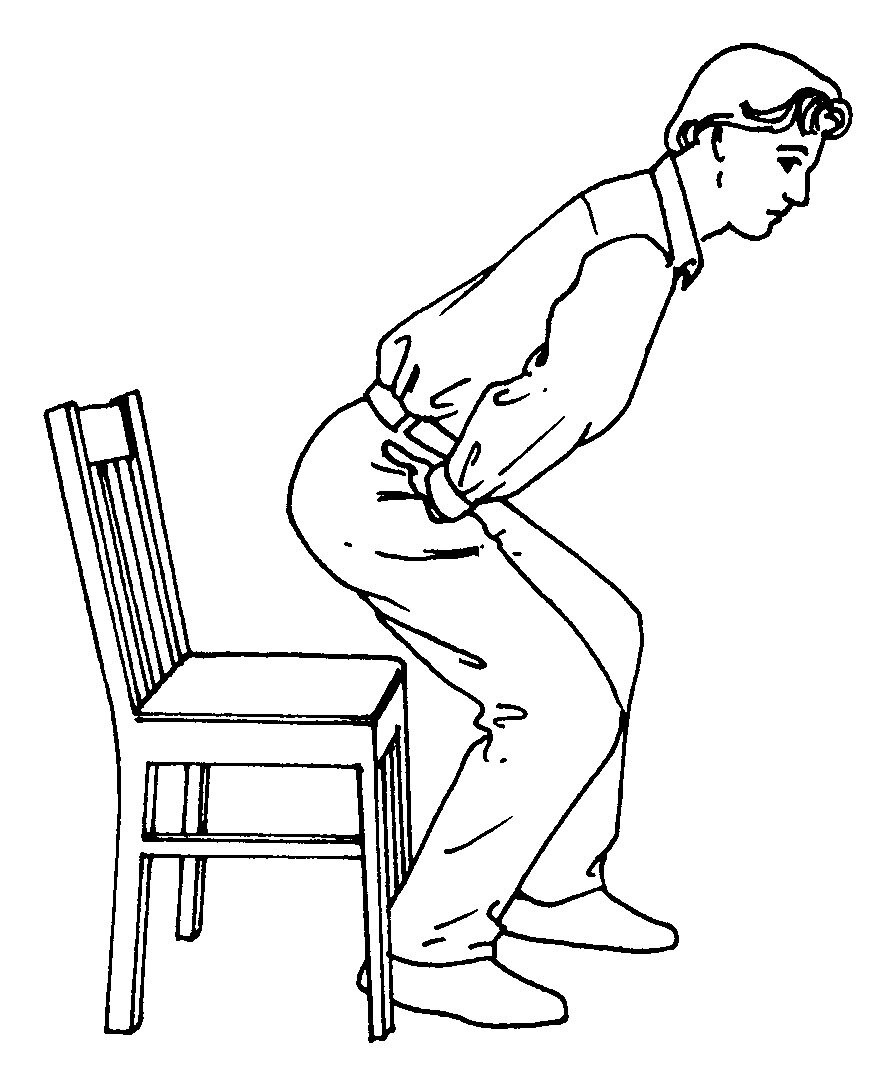

Then as you begin to stand, do you orient your face down? Why? Since you want to stand up, what if you looked forwards and reached your mouth and head in the direction you want to move? Does that make it easier? You could even reach your arms out in front of you as you reach your face forward and rock up to your feet.

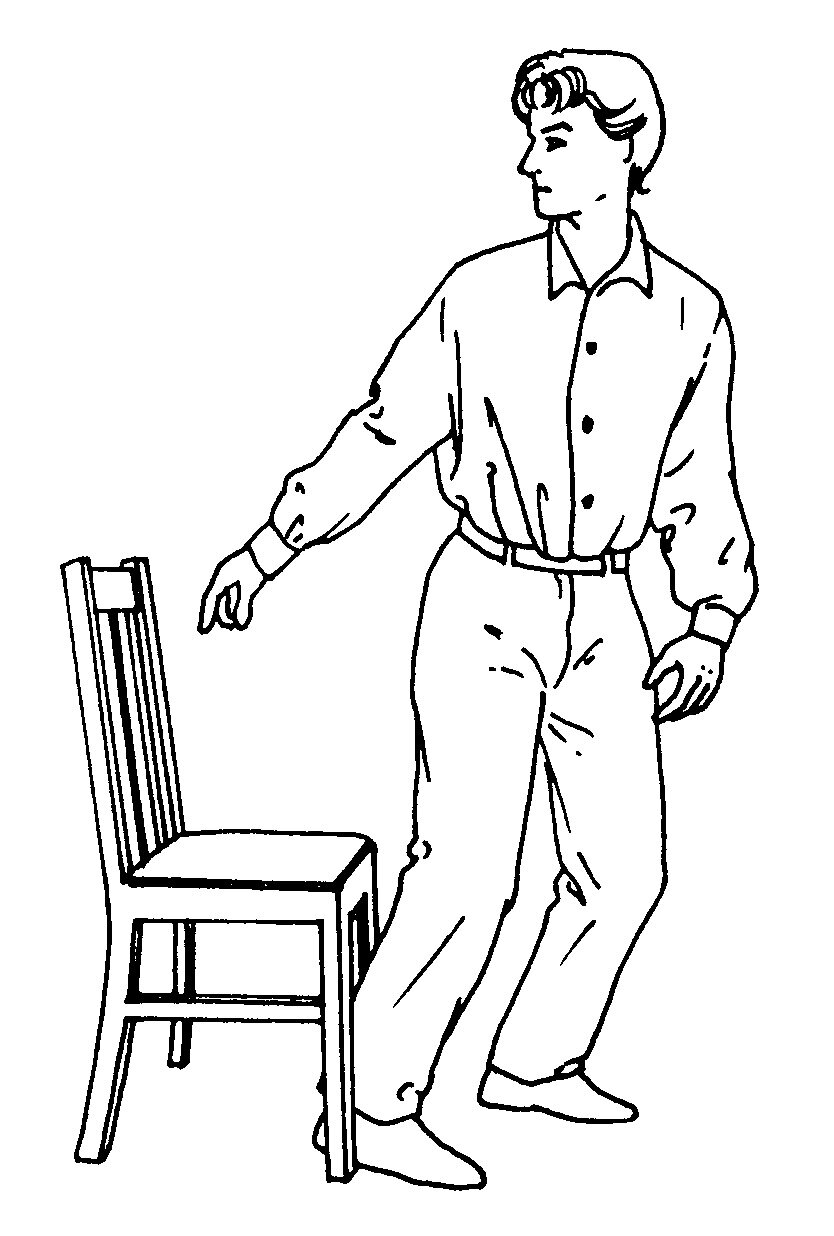

How about sitting back down? Could you reverse the act of standing in order to sit down? This means if someone took a series of photos of you moving from sitting to standing, you couldn’t tell if they were photographing you from standing to sitting because the movement is completely reversible. Standing up and sitting down would have the same shape.

You could further explore how wide you want your legs apart, if you want your feet pointing forwards or out to the side.

Additionally, do you have a habit of using your arms to stand up? If you eliminate pushing off the armrests, you’ll naturally develop strength in your legs, coordinated with your balance.

Finally, do you breathe in or out when you come to standing? Perhaps a better question, do you breathe? Or do you clench your throat and tighten your diaphragm as if you were lifting a heavy object? This is called the Valsalva maneuver. If we become aware of and eliminate those unnecessary Valsalva contractions, we can breathe and move more easily.

This exploratory approach to movement and rehabilitation—Sensercise—is the way to recover after an insult to the body as well as the way to achieve greater coordination and mobility in general. With Sencercise, you can better experience your body and your life—and to enjoy any activity.

-Frank Wildman, PhD