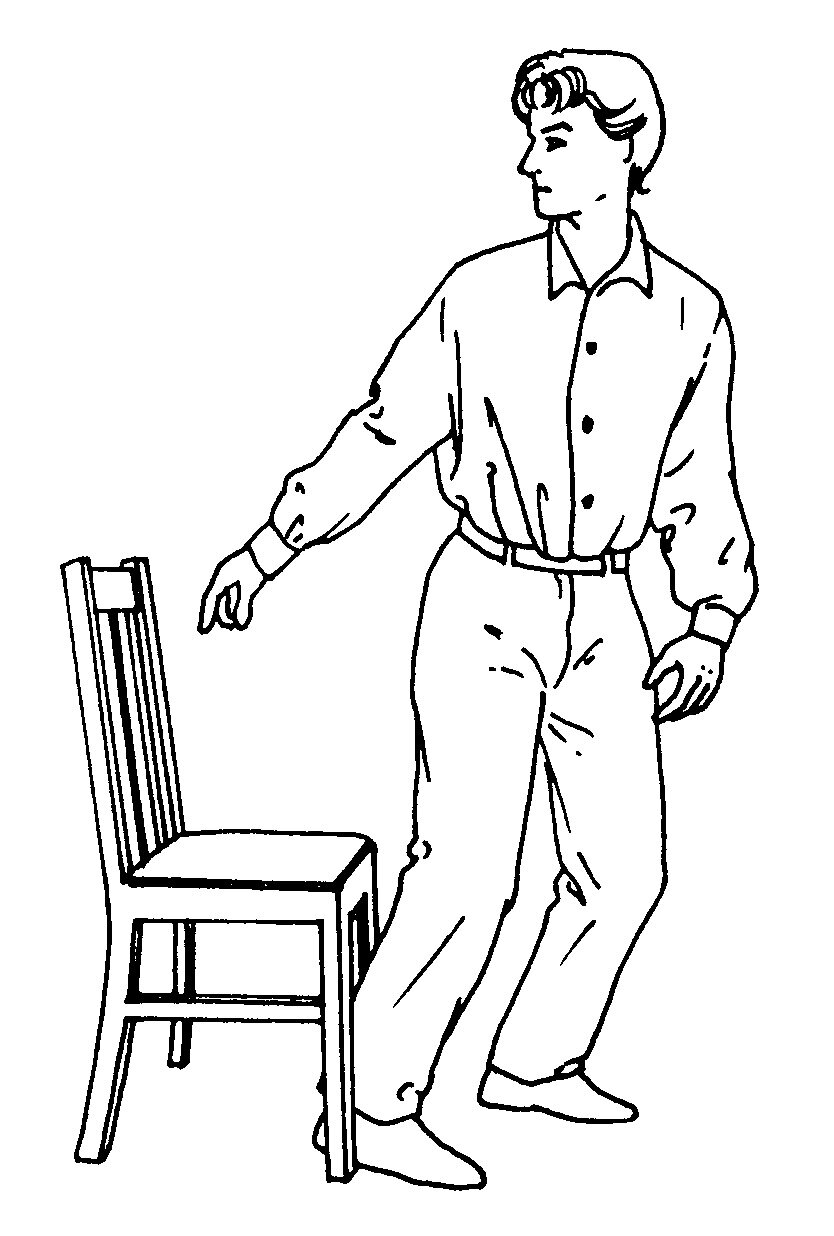

The purpose of “The Pelvic Walk” is to help you discover how to sit more lightly, move your pelvis more easily while sitting, and turn in your chair while performing activities in the workplace or home

1. Sit comfortably in the middle of your chair without leaning back. Make sure your feet are flat on the floor. Feel yourself sitting as tall as possible. Separate your hands and rest the palm of each hand on your thighs.

✓Awareness Advice:

Make sure you don’t slump in your chair as you progress through the movements. To heighten your sensation of the movement, you can close your eyes, but remember to maintain a physical attitude of being upright and looking outward.

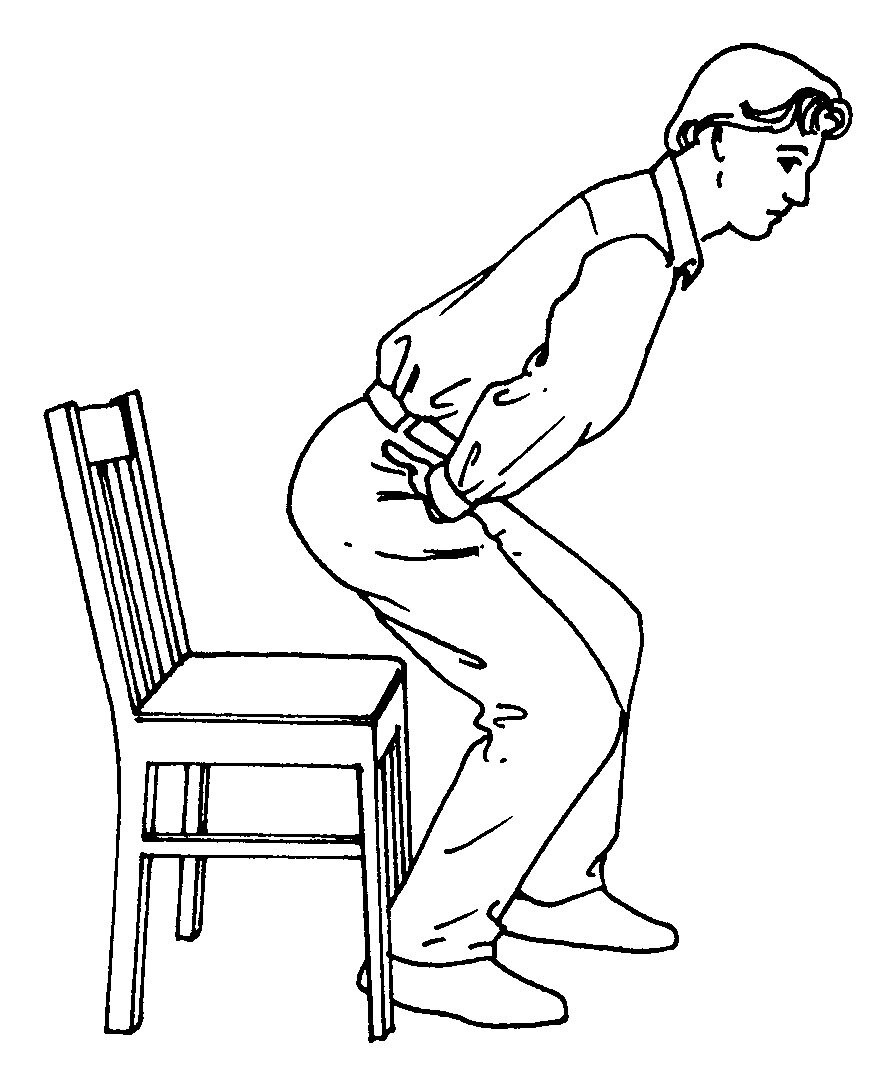

2. Slide the right side of your pelvis forward in the chair as if you wanted to reach straight ahead with your right knee. Then, slide your pelvis and leg back in the chair. You will be pivoting on your left buttock and sitz bone. Repeat this movement several times until it becomes lighter and more comfortable. Rest briefly and then return to your starting position.

✓Awareness Advice:

Be sure that the work performed in these movements is done with your torso. Keep your feet flat on the floor and do not push too hard with your legs.

3. Repeat the same movement moving the left buttock and thigh forward and backward, pivoting on your right side. Which side glides more easily on your chair?

4. Explore each side again and observe how much your head and shoulders turn. Rest briefly and then return to your starting position.

5. Keeping both feet on the floor, lift the right side of your pelvis off the chair and bring it back down. Do you tilt your whole body to the left, or can you do the movement shortening the right side of your waist and keeping your head approximately in the center?

✓Awareness Advice:

If at any point you cannot feel the movement clearly, or cannot perform it to your satisfaction, stop, close your eyes and imagine performing the movement. Then imagine what it would feel like if you were moving and picture the movement happening.

6. Repeat the movement on the other side. Again, which side is easier? Rest.

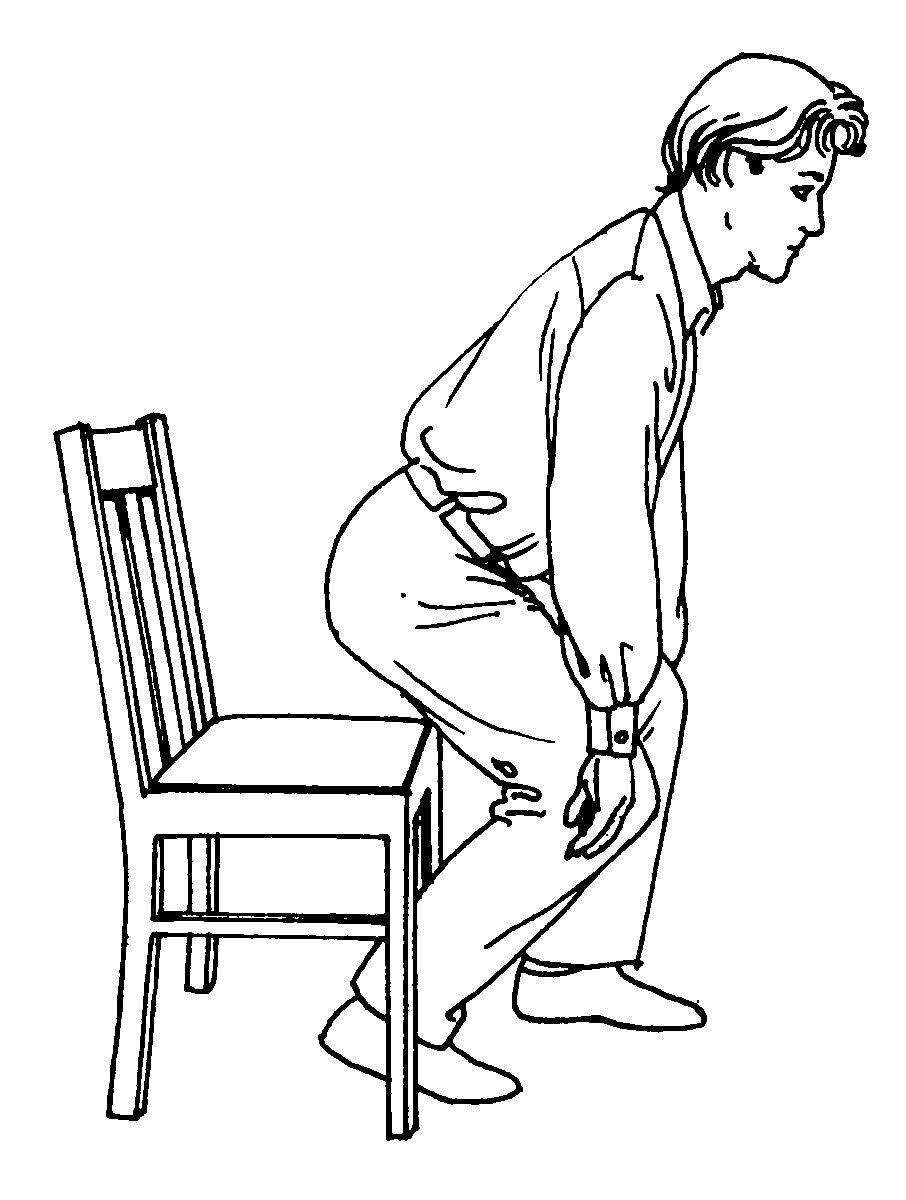

7. Return to your starting position in the middle of your chair and place your hands on your knees and walk your buttock forward. Then walk the other side forward until you reach the edge of your chair. Then walk your pelvis backward. As you walk your buttocks forward and backward in your chair, make the movement easier.

8. Return to sliding each side of your pelvis forward and backward alternately while looking straight ahead. Work to make the movement easier as you slide one side after the other

-Frank Wildman, PhD

This “Pelvic Walk” exercise is excerpted from the book, The Busy Person’s Guide to Easier Movement, by Frank Wildman, PhD, which has common-sense lessons connecting the mind and body through movement to help people move with more ease, comfort and efficiency.