The older we get, the more clever we must become.

Old age, for most people, is a time of increasing physical discomfort, stiffness, and fatigue. Everyday activities like walking up a flight of stairs or carrying groceries becomes more and more difficult. To counteract the process of apparent bodily decline, older people are told to perform traditional forms of exercise designed to strengthen muscles or increase endurance. This seems sensible and obvious, and indeed contemporary research points to the benefits of strengthening, flexibility, and endurance exercises for the elderly patient. But traditional exercise programs often involve a degree of strain, fatigue and regimen that many older people are unwilling to partake in. A seventy-year-old woman who has difficulty with degenerative joint disease is neither ready for, nor enthusiastic about jogging or weightlifting.

After a certain age, our bodily wisdom tells us it’s too difficult to slam our bones, strain our muscles, and do the things we used to do with will power and brute strength. But as we age, it is more important to use our bodies more efficiently. We must improve our quality and ease of motion, our coordination, our sense of balance, control and comfort. Unfortunately, little in our fitness culture encourages us to learn how to reduce stress while increasing muscular efficiency in a pleasurable and comfortable manner. Because of this, it is not common for people in their 50’s, 60’s, 70’s and older to explore new ways of moving as we did when we were infants, which is really the key for continued coordination.

An infant’s body and its capabilities are quite different from those of a five-year old, a teenager, or a 40-year old. However, most people continue through life with the same movement patterns that we taught ourselves in the years between birth and when we considered our mobility good enough to do whatever we wanted to get around in the world (i.e., walk, run). If an individual was interested in athletics, there would be further training, but often with little regard for how the body actually works, such that success at sports was usually understood to be the result of talent and hard work, rather than wisdom about how to use the body efficiently.

Proceeding through life with the same set of movement habits developed and codified at age three, it's not surprising that eventually those neurological habits will no longer be applicable to a changed body. As these ingrained habits become less efficient with an aging body, a natural reaction is to try harder to ingrain and repeat these patterns.

The work of Dr. Moshe Feldenkrais offers a thorough application of current models and approaches to motor learning and motor control in order to change our ingrained movement habits. Movement lessons invite a student or patient to recreate the childhood experience of learning to organize and control all the body’s movements, including all aspects of interacting with the environment and what one has to do to move through that environment. The lessons provide an innovative and exciting movement program that can enhance your ease of movement, flexibility, relaxation, and posture faster and further than any form of conventional exercise.

Focusing our awareness on how we move

Dr. Moshe Feldenkrais systematized the process of paying attention, a rare and necessary element in the process of growth and change. The lessons begin with the proposition that correct movement is movement with minimal effort, and that most people have learned to move incorrectly by straining with more than the needed effort to do what is required. The goal of the lessons is to call into awareness the basic movement habits that cause stress, and then to systematically release the body into more effortless motion.

For example, when most people, especially the elderly, move from a lying to a sitting position, whether in bed or on the floor, they strain their abdominal and neck muscles. I would work with this person to retrain them to sit up by first becoming aware of exactly how they strain and where the focus of tension is, and then by altering the dynamic pattern of the movement, so as to reduce fatigue. Rather than repeatedly doing sit-ups, a person learns how they sit up and how many different ways they can sit up, while learning how to sit with less effort.

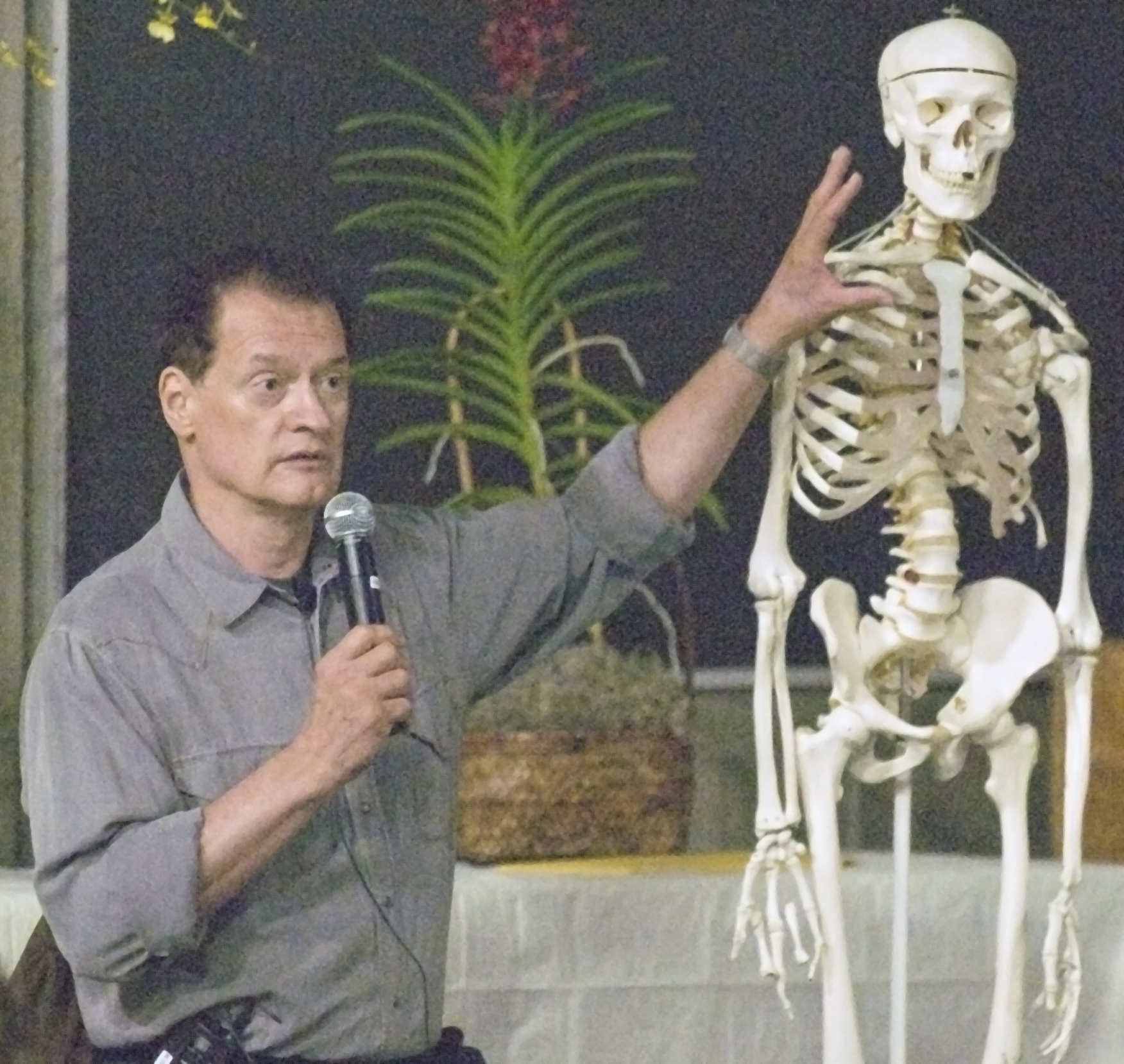

At a movement program for older adults presented through the University of California, I introduced students to gentle and intriguing movement lessons developed by Dr. Moshe Feldenkrais. The results were astonishing.

The majority of the people in the class believed their physical limitations and difficulties were the inevitable result of aging. They had a self-image of pains that don’t improve, rigidities, and movement limitations. They had come to the class with the idea of exercising their limited bodies to develop enough strength and flexibility to continue on, but only within the same essential body image. But instead of straining, groaning, and stretching, they learned stress-free interesting movements that were easy to do and, most importantly, changed the way they understood and used their bodies.

There were striking changes during the course of the program. In the first class, many participants needed help getting to the floor and even more needed help in standing. Lying flat on the firm floor was a painful experience for many. By the tenth class, people simply got down to the floor and up by themselves. During class, they lay flat on their backs without pain, some for the first time in decades.

The results of this class reached beyond improved posture and muscular efficiency, as the students gained an awareness of how to use their bodies better. They were able to perform tasks previously accomplished with much force but little skill, for example, standing up from a chair. It doesn’t take much leg strength if done properly, if there is an understanding of the relationship of legs to back to pelvis to shoulders to head. However, if someone does not have a clearly felt image of the relationship between body parts, it can be an extraordinarily difficult task. The less information we have about how to coordinate a simple action, like standing from a chair, the more effort it takes.

The renewed awareness was often life changing. Some people had stopped going out alone because they feared they would tire or lose their balance or not be able to get up from sitting without asking for help from a stranger. When they learned how to get out of a chair in a balanced, smooth fashion, they were amazed. Some cried. The world had opened up to them again.

While anyone would benefit from learning how to sit up more efficiently, it is older people who need such training the most. As strength and stamina decline, it is necessary to learn how to make the best use of available energy. To address the needs of the older population, I recommend gentle and innovative movement lessons to introduce new ways of moving, and thinking about moving- anti-exercise for the older and wiser.

If you are interested in working privately, please email me at frank@frankwildmanmovement.com or call 510-283-5494.

Click here for one of my sample movement lessons, Freeing Your Middle Back.

-Frank Wildman, PhD